Rashōmon’s ruined gate, a central element in Ryūnosuke Akutagawa’s story “Rashōmon,” held a notorious reputation in 12th-century Kyoto. It served as a haven for thieves and miscreants, symbolizing societal decay.

Akutagawa harnessed this setting’s bleak symbolism to enhance the moral undertones of his narrative. Filmmaker Akira Kurosawa later adapted elements from two Akutagawa works — “Rashōmon” and “In A Grove” — in his 1950 Jidaigeki drama “Rashomon.” Kurosawa transformed the gate into a pivotal location, embodying moral ambiguity and the coexistence of despair and hope.

The film opens with three men seeking refuge from heavy rain under the ruined gate, sparking a retelling of a murder mystery through conflicting perspectives. These varied accounts leave the truth elusive, posing profound questions about human perception.

Kurosawa’s Masterpiece and Its Intricacies

Akira Kurosawa’s “Rashomon” is often hailed as a cinematic masterpiece, largely due to its exploration of human nature and the complexity of truth. Pushing the concept of unreliable narration to its limits, Kurosawa crafts a deceptively simple yet intricate tale.

This story unravels in a manner that defies conventional narrative structures, amplified by Kazuo Miyagawa’s evocative cinematography, which uses light and shadow to heighten tension. The film’s open-ended conclusion leaves viewers pondering its themes long after it ends.

While “Rashomon” may lack the layered complexity of Kurosawa’s “Throne of Blood” or the surreal beauty of “Dreams,” it remains an extraordinary exploration of the human condition, demonstrating how film can magnify life’s most intricate aspects.

Examining Truth in a Web of Deception

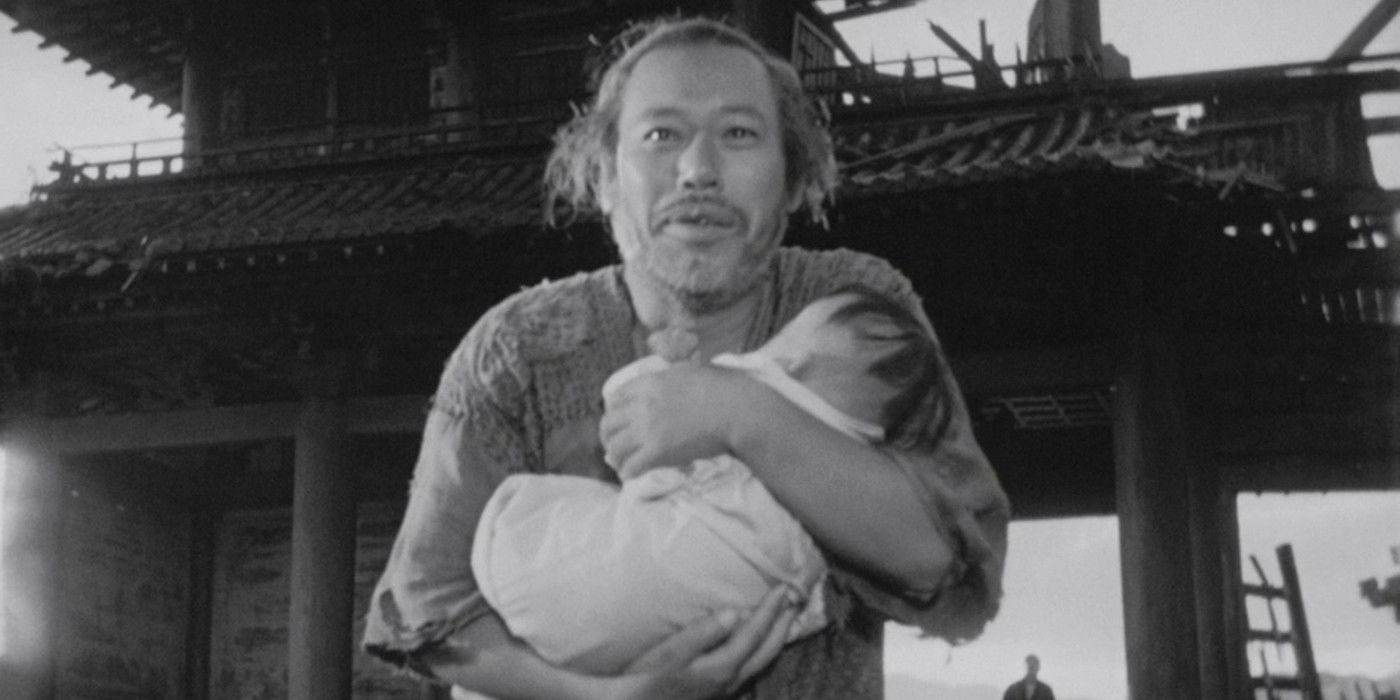

The events in “Rashomon” unfurl through layered recounting, each witness offering a unique perspective on the same incident. A woodcutter (Takashi Shimura) narrates a tale of murder and sexual assault to a priest (Minoru Chiaki) and a commoner (Kichijiro Ueda), revolving around a samurai (Masayuki Mori), his wife (Machiko Kyō), and a bandit (Toshirô Mifune).

Each testimony diverges dramatically, with even the deceased samurai presenting his version of events through a psychic. This fragmented narrative prevents any clear resolution, leaving the audience to grapple with the absence of definitive truth.

Kurosawa’s refusal to deliver a conclusive verdict encourages viewers to form their interpretations. Fiction often invites analysis, but “Rashomon” actively challenges audiences to confront the intricacies of deception and self-interest.

The characters address the camera, pleading their cases, which exposes the self-serving motives behind their narratives. Kurosawa’s work underscores the human tendency to distort reality for personal gain, illustrating how even the dead cannot escape this compulsion.

The Rashomon Effect: Perception Shapes Reality

The film’s depiction of truth as subjective is encapsulated in the so-called Rashomon Effect, where personal perception colors reality.

Each witness offers a version of events shaped by their biases and motivations, including the woodcutter, whose initial omission of key details reflects his instinct for self-preservation.

Though his later testimony may appear more objective, it, too, is influenced by his own interests. The setting changes between the gate, the forest, and a sparse courtroom, creating a disorienting juxtaposition.

The forest, where the crime occurs, brims with tension, becoming a stage for violence, passion, and control. Kurosawa weaves these elements together into a narrative puzzle that resists resolution.

The final question is whether any objective truth exists or if all recollections are inherently flawed performances. These layers force the viewer to confront their own perceptions, reinforcing the idea that truth is subjective and elusive.