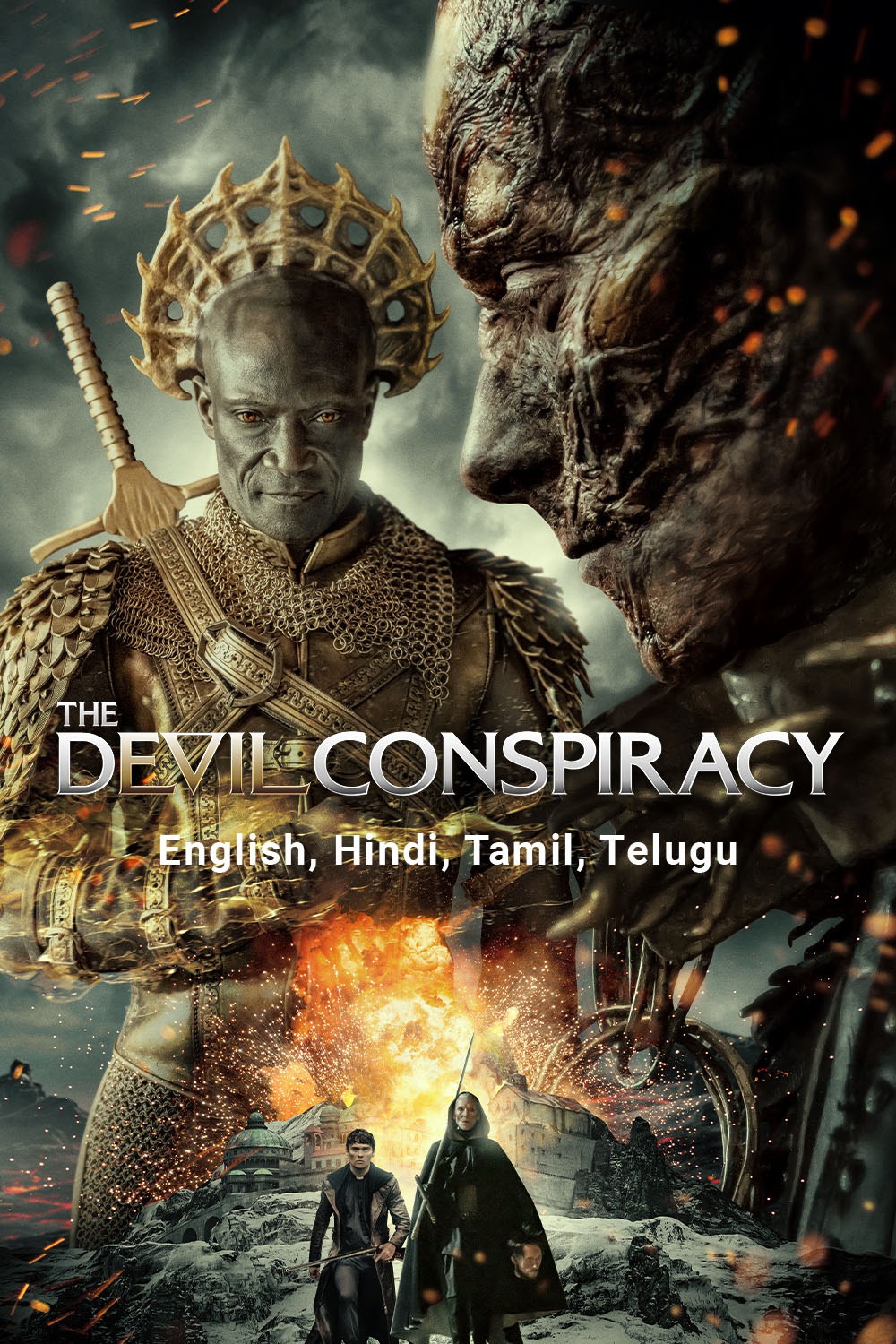

A technological twist enriches the age-old conflict of good versus evil in the religious action thriller “The Devil Conspiracy.” Canadian director Nathan Frankowski, alongside first-time screenwriter Ed Alan, narrates the story of Laura (Alice Orr-Ewing), an American art student and firm atheist in Turin.

Her life is irrevocably altered when she becomes embroiled in a nefarious cult’s plot to liberate Lucifer (Joe Anderson) and his legion of demons from hell to wreak havoc on Earth.

Her sole chance for salvation lies in heaven’s mightiest warrior, the archangel Michael, who descends to Earth in the guise of a recently slain young priest (Joe Doyle).

A blend of various influences characterizes the film, referencing everything from the “Omen” series, particularly its New World Order-themed sequel “The Final Conflict,” to “The Exorcist,” “Terminator 2,” and contemporary superhero movies.

Alan’s screenplay posits that the angels and demons depicted in religious art—presumably including those seen in this film—are not mere allegories for human experience but tangible beings engaged in a genuine battle.

By the conclusion, Lucifer is once again confined by his arrogance and pride. However, horror enthusiasts understand that no formidable monster, particularly the most notorious one, is ever truly vanquished. This analysis will explore the climactic moments of “The Devil Conspiracy,” highlighting both its exhilarating peaks and confusing troughs.

Central to the film’s plot and the satanic cult’s wicked agenda is the Shroud of Turin. This long piece of linen, bearing a man’s bloodstains and outline, is widely believed by some to be the burial cloth covering Jesus after his crucifixion and before his resurrection.

The film’s narrative kicks off when the Shroud is publicly displayed for the first time in decades at St. Michael’s Cathedral in Turin. Seizing this opportunity for exposure, Lucifer’s followers infiltrate the Cathedral under the cover of night, stealing the Shroud, murdering young Father Marconi (Doyle), and taking Laura hostage.

For the film’s premise to hold, viewers must accept several assertions: that the Shroud is an authentic relic of the resurrection, that Jesus’ DNA resides in what appears to be blood stains, and that this DNA could be extracted to create a clone of Jesus.

While the last point leans into science fiction absurdity (at least, for now), the first two claims have sparked debate for centuries. Historical and scientific evaluations of the Shroud generally trace its origins back to the 13th or 14th century, labeling it a forgery created over 1,000 years post-Jesus’ death.

Nonetheless, many religious believers maintain its authenticity and power as a symbol of faith. Within the film’s context, the Shroud is treated as genuine; not even skeptic Laura questions its validity. Accepting the Shroud’s history, at least for the sake of the story, becomes a prerequisite for the audience.

Saint Michael Vanquishing Satan

In line with the film’s overarching theme of the literal power of imagery, the Shroud serves as a MacGuffin. Early on, Father Marconi shares with Laura his belief that art functions as both a historical record and a future guide—an oversimplified view of art’s value and purpose (particularly religious art) that nevertheless supports the film’s thematic direction.

Frankowski draws upon imagery from both sacred and secular domains, most prominently the Catholic motif depicting Saint Michael triumphing over Satan.

The film opens with a dramatization of this event, featuring actor and martial artist Peter Mensah as Michael in his divine form. Later, as Laura sketches a sculpture of this celestial confrontation—complete with a removable sword for unclear reasons—Satan’s head appears to animate slightly, just beyond Laura’s peripheral vision.

Throughout centuries, Saint Michael’s struggle against the devil has frequently inspired Renaissance art. The most famous representation is likely Raphael’s early 16th-century painting, which portrays a winged Michael atop Satan in victory, sword at his hip and spear poised over the devil’s head.

Numerous other artworks have adopted this foundational pose over the centuries, often depicting Michael bearing golden chains to bind Lucifer. The film incorporates both the sword and chains into its plot, as they are the very tools that keep Lucifer imprisoned in hell until a mysterious earthquake loosens the chains, inching him closer to liberation.

Blood Libel

So, who exactly aids Lucifer in his quest for dominion? Naturally, a merciless cabal of elite child-sacrificing figures emerges! Represented by a ubiquitous inverted triangle emblem, this group masquerades as an innovative biotech firm run by the sinister Dr. Laurent (British actor Brian Caspe).

Behind the scenes, the true masterminds are the white-haired Liz (dancer Eveline Hall) and the mute, monstrous Beast of the Ground (Spencer Wilding). Throughout history, the dread of innocent Christian children being victimized by ritualistic sacrifices has ignited conspiracy theories and violence.

In the 1980s, this fear manifested in “Satanic Panic,” where heavy metal music and Dungeons and Dragons games served as evidence of the devil’s corrupting influence. More recently, QAnon and Pizzagate conspiracy theories have implicated prominent politicians and celebrities in fabricated sex abuse cults.

The origins of these contemporary panics can be traced back to “blood libel,” the enduring belief that Jews use Christian blood in their food and religious rites, leading to anti-Semitic violence worldwide.

While Alan’s screenplay does not explicitly reference blood libel, history illustrates that the notion of a dark conspiracy orchestrated by affluent globalists often has anti-Semitic roots; audiences need only read between the lines.

Just before the moment Laura/Lucifer gives birth, as Michael lies gravely wounded and evil seems to have triumphed, she cradles his body in her lap.

Frankowski presents this scene directly, and the reference is unmistakable: it parallels La Pietà, Michelangelo’s renowned sculpture of the Virgin Mary holding Jesus’ lifeless body post-crucifixion.

Like Saint Michael vanquishing Satan, this visual reference is clearly intentional, though the values have been reversed. Instead of a moment filled with love and solace, this scene conveys hatred and defeat. Within the film’s context, it carries an almost humorous undertone.

Despite the potential for campy entertainment, “The Devil Conspiracy” offers little humor; nearly every scene maintains a serious tone, much like Michael, who embodies an archangel crossed with a Terminator.

Attempts at levity often manifest as trivial quips, such as when Lucifer laments, “Was that really necessary?” as Michael chains him to a rock at the dawn of time.

Occasionally, however, a spirit of wit emerges, such as during Laura and Michael’s Pietà homage or when Michael drives in the late Father Marconi’s car while the INXS classic “The Devil Inside” plays on the radio. He changes the station, landing on Real Life’s “Send Me an Angel.”

No One Must Know

At last, Lucifer’s human vessel is born. Liz presents the shrieking newborn to Dr. Laurent and the other cult members, who kneel in awe. Unbeknownst to them, their part in the devil’s conspiracy is about to conclude.

By Lucifer’s command, no one must be aware of the events that transpired within this stronghold, prompting the Beast of the Ground to employ his favored weapon—a razor-sharp triangular blade linked to a long chain—to brutally slay every cult member, including the unfortunate Dr. Laurent, who likely believed he had secured his place in the devil’s good graces.

Prior to this moment, the film featured a considerable amount of violence, albeit in a PG-13 superhero style where individuals are beaten or shot without displaying much visible pain or injury, and very little blood.

This scene, however, changes dramatically, and the abrupt transition to graphic horror and visceral gore inevitably evokes comparisons to the 21st century’s most infamous religious film, Mel Gibson’s ultra-violent Easter depiction “The Passion of the Christ.”

Even before that, biblical epics have often indulged in depictions of sex and violence under the guise of history or moral messaging, from Cecil B. DeMille’s early works to Bruce Beresford’s decapitation-filled version of “King David,” starring Richard Gere. It seems the tradition of infusing Old and New Testament narratives with excessive bloodshed and gore is as old as Hollywood itself.

Returning to the Cathedral of St. Michael with the Shroud and the baby, Laura and Cardinal Vincini confront the hapless Bishop Bustamante (Pavel Kriz) as he delivers a homily about the existence of angels and demons and the necessity of recognizing their literal presence in the modern era.

His voice falters when he beholds this unlikely pair returning with the Shroud, and upon noticing the baby, he can only inquire, “What child is this?”

Laura, whose hair fell out during the pregnancy as Lucifer drained her energy, wears a shawl to cover her head. The once carefree young atheist has transformed into a grave mother, burdened with cosmic responsibilities.

This moment not only echoes the film’s beginning, where Laura argued with her predatory professor and Father Marconi that Catholic art must be metaphorical since angels and demons are not real, but it also reinforces the film’s central themes of sacrifice and the literal interpretation of religious art—and by extension, scripture.

Another Devil Conspiracy?

Yet, neither Laura nor the Cardinal is fated to live their lives in gloom and baldness. The film’s final scene leaps forward several years, showing the two joyfully playing in the woods with a young dark-haired boy named Michael.

As explained earlier, Lucifer’s downfall stemmed from his own pride. He believed himself equal to God, asserting that only Jesus’ mortal form could contain him.

In a way, he was correct. Jesus’ body was indeed the sole vessel strong enough to confine Lucifer—until now. Having given birth to a son who bears the same name, Laura finally has the divine energy to bind Satan in chains.

The movie’s final twist is almost comically simple: her baby is the true Messiah. In that moment, it becomes clear that Laura and Michael possess the power to defeat evil, reversing the roles of the historical battle depicted throughout the film.

Despite its flaws and a somewhat convoluted plot, “The Devil Conspiracy” raises questions regarding the nature of evil, sacrifice, and redemption.

By tackling the timeless struggle between good and evil through a modern lens, the film manages to engage viewers, encouraging them to reflect on their beliefs and the narratives that shape them.

As the credits roll, audiences are left pondering the delicate balance between light and dark, and how their understanding of art, faith, and history informs their perspective on the world.