Ingmar Bergman’s Persona (1966) stands as one of the most intriguing works from the director’s highly creative filmmaking period, which had its strong foundation in the Faith Trilogy—Through a Glass Darkly (1961), Winter Light (1963), and The Silence (1963).

Film professor and historian Thomas Elsaesser once remarked that attempting to write about Persona has been as challenging for film scholars as climbing Mount Everest is for mountaineers. Despite running for less than 90 minutes, this minimalist psychological drama distorts reality.

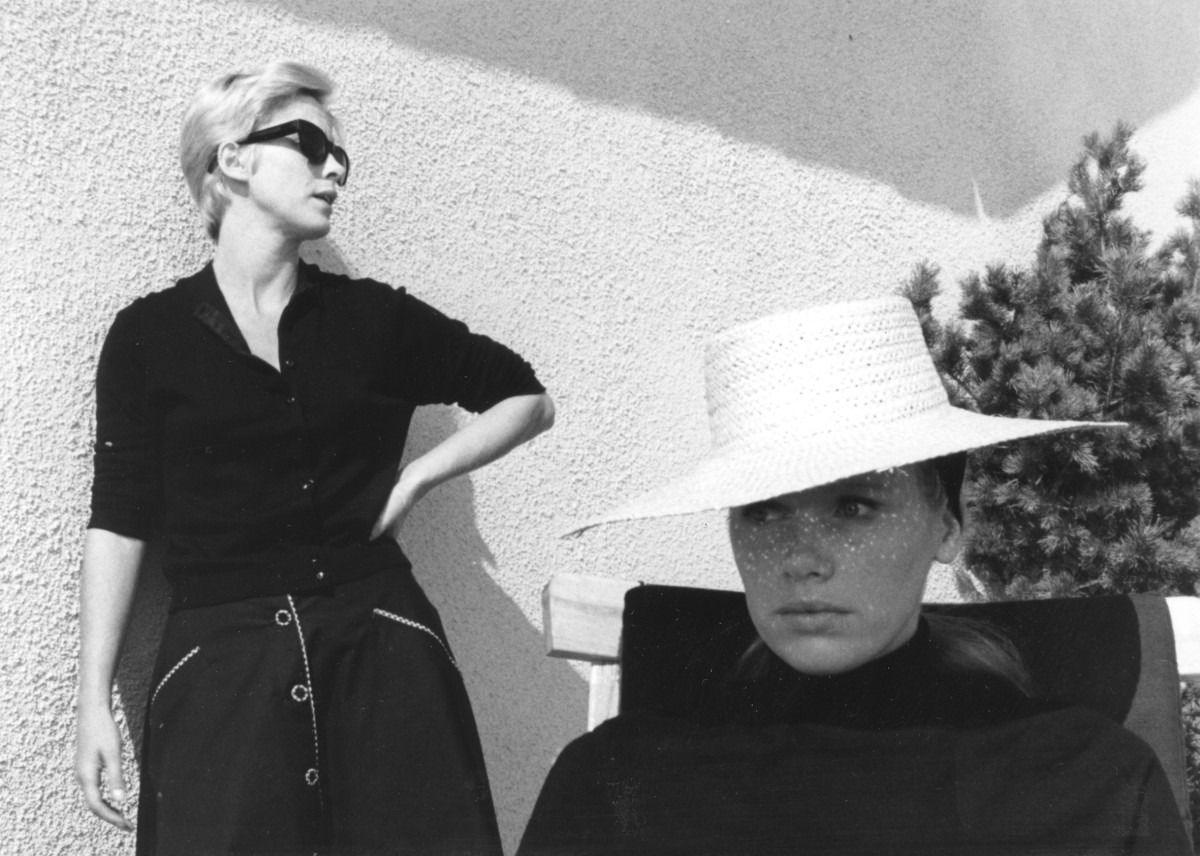

The Evolving Relationship Between the Nurse and the Patient

The highly expressive nurse recounts a past event when she and Karl-Henrik rented a seaside cottage. On a day when Karl-Henrik went into town, Alma ventured to the beach alone. There, she encountered Katarina, a girl from a neighboring island.

The two women, wearing straw hats, lay sunbathing without any clothing. Before long, Alma became aware of two figures lurking above them—a pair of boys who were peering down from behind the rocks. When she mentioned their presence to Katarina, her companion showed little concern.

Not long after, the bolder of the two boys approached and sat beside Katarina. Katarina then initiated an intimate encounter, leading the boy to engage in sexual intercourse with her.

Following this, Alma called the boy over, and in a moment of reckless abandon, he released his seed inside her before she could stop him. The situation escalated further when the second boy joined in and engaged in oral sex with Katarina.

Later that night, Alma was intimate with Karl-Henrik, experiencing pleasure that she had never felt before or since. This encounter led to an unplanned pregnancy. Since neither of them was ready for a child, she underwent an abortion.

While recalling these events to Elisabet, Alma, overwhelmed with emotion, admits to the guilt she carries, even though the choices are her own. She then begins to reflect on the two opposing sides of her personality, hinting at the deeper conflict to come.

Even in a drunken state, she continues to ponder their identities, remarking on how similar they appear and how easily she could take on Elisabet’s persona, although, as an actress, Elisabet would find it far simpler to become Alma.

Alma’s Discovery in Elisabet’s Unsealed Letter

What follows takes on an almost dreamlike quality for Alma. First, both she and the audience hear Elisabet’s voice saying, “Go to bed, or you’ll fall asleep at the table.” Since Elisabet’s face isn’t visible when she speaks, it raises the question of whether Alma only imagined hearing her voice.

Later, Elisabet enters Alma’s room like an apparition, embracing her and gently touching her face. Their eyes lock directly onto the camera. The next morning, when Alma confronts Elisabet about whether she spoke the night before or visited her room, Elisabet simply shakes her head to deny it.

Later that day, while driving to town to mail some letters, Alma notices that one of the envelopes, addressed to the doctor, has not been sealed. Unable to resist, she reads its contents. In the letter, Elisabet describes “the fun of studying Alma.”

She recounts details of the orgy and the abortion, pointing out that Alma’s expressed beliefs do not align with her actions—essentially using Alma’s own words against her. Reading this infuriates Alma, as she realizes that Elisabet has assumed a position of superiority, treating her as a mere subject for observation.

The intended caregiver has, in a cruel twist, become the one under scrutiny.

Does the Final Monologue Expose Elisabet’s Struggles with Motherhood and Identity?

A man’s voice calls out for Elisabet, and Alma hears it. It belongs to Mr. Vogler (Gunnar Björnstrand), Elisabet’s husband, who mistakenly identifies Alma as his wife. Even as Alma tries to correct him, he remains convinced.

Eventually, Alma begins to embody Elisabet, while the real Elisabet remains silent and distant, merely observing the interaction. As Alma, she offers Mr. Vogler warmth and reassurance, even asking about their child and requesting that he buy the boy a toy.

This moment of tenderness soon leads to intimacy, with Elisabet watching it all play out. Yet, despite Mr. Vogler’s tight embrace, Alma murmurs, “I’m cold and rotten and indifferent.

It’s all just a sham and lies,” revealing how deep-rooted insecurities and existential despair inevitably surface, even when assuming someone else’s role. After Alma’s confrontation with Elisabet, the sense of time becomes uncertain, making it unclear what is real and what exists solely in the minds of the characters.

Eventually, Alma revisits a topic that had unsettled Elisabet—her torn-up picture of a child. What follows is a monologue that plays out twice, though spoken by Alma, narrating Elisabet’s own story. It reflects the common experience of women who are expected to adopt the role of a nurturing mother.

Feeling pressured by a comment about her perceived lack of maternal instincts, Elisabet chose to become pregnant. However, once she was expecting, she felt immense regret, burdened by the realization that motherhood would forever tie her down.

She had attempted to end the pregnancy herself but was unsuccessful, and, she gave birth to a son.

Is Alma a Reflection of Elisabet’s Inner Turmoil?

Although Elisabet battled with guilt and a deep sense of repulsion, she rejected the role of a mother. As she returned to her career in theatre, the child was raised by relatives and a nanny.

However, the boy’s unwavering love for his absent mother only intensified Elisabet’s emotional torment, as she feared she could never truly reciprocate those feelings. The opening scene, where the boy reaches out to an unresponsive image of his mother, takes on a deeper meaning in light of this revelation.

Yet, this second monologue ends differently, with Alma asserting, “No, I’m not like you. I’m Sister Alma. I’m only here to help you.” This moment is visually reinforced by a spliced shot of both women’s faces, their left and right halves merged, making them appear as two sides of the same person.

This raises the possibility that Alma might be a manifestation of Elisabet’s subconscious, given that Elisabet has chosen silence, perhaps as a way of suppressing the maternal role she could never fully embrace.

Following the monologue, Bergman presents a striking visual—both women looking downward in silhouette. Alma, still dressed as a nurse, declares, “I’ll never be like you. I change all the time. You can do what you want. You won’t get to time.”

This statement suggests that Alma and Elisabet represent opposing forces within a single psyche, with one persona attempting to banish the other—along with all its fears and uncertainties—into the depths of the subconscious.

Does “Persona” Blur the Boundaries Between Reality and Identity?

Alternatively, they might be entirely separate individuals, with Alma, having gained insight into Elisabet’s hidden fears and suppressed frustrations, making the conscious choice to distance herself from the actress. In doing so, she comes to terms with her insecurities, allowing for a more grounded perspective.

Bergman’s Persona is deliberately shrouded in ambiguity, offering no definitive answers. The final scenes—Elisabet on a film set and Alma leaving the island on a bus—only further complicate the perception of what is real.

As the images fade and the projector halts, it suggests that what the audience has witnessed is an artificial construct of reality. This reinforces the idea that breaking into the characters’ true reality is an impossible task.

Persona remains an endlessly thought-provoking and deeply elusive film, examining identity, memory, and the nature of the self.

At the moment, you are able to watch Persona streaming on Max, Max Amazon Channel, and Criterion Channel.