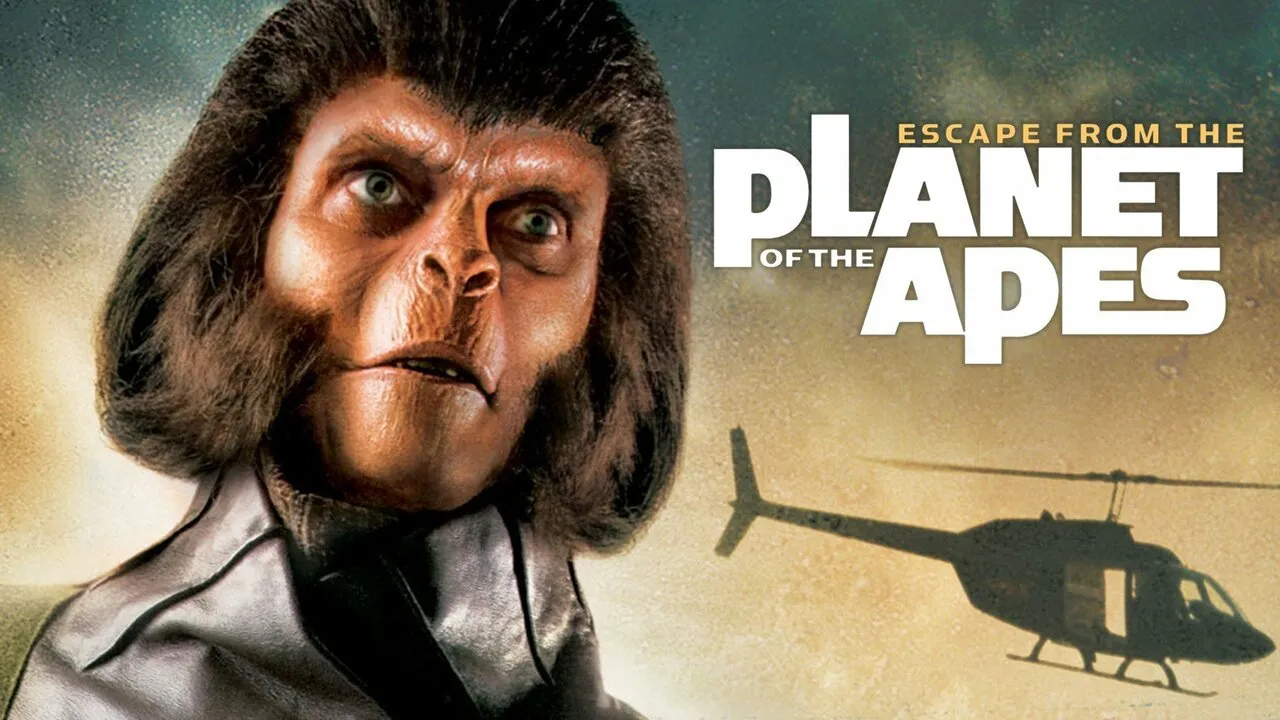

The third installment in the Planet of the Apes series, Escape from the Planet of the Apes, was released by 20th Century Fox 46 years ago. The fact that another sequel came after Beneath the Planet of the Apes was an unexpected outcome, considering the conclusion of the previous film, which had ended with the destruction of Earth.

However, Beneath performed remarkably well at the box office, earning $19 million on a budget of just $4.6 million. This success led to a simple, yet impactful, message being sent to screenwriter Paul Dehn: “Apes exist. Sequel required.”

Dehn’s response was nothing less than ingenious, expanding the storyline into a cycle that continued with Escape from the Planet of the Apes. This film works as a sequel, prequel, and reboot all at once. While these terms weren’t in use back in 1971, the film managed to integrate them into a successful continuation of the saga.

Alongside a strong script and clever direction by Don Taylor, the film benefited from excellent performances by Kim Hunter and Roddy McDowall, bringing the series to new heights. The final scenes of Beneath had set the stage in the far future.

Where an intelligent ape civilization was locked in a deadly battle with telepathic human mutants living underground, while Charlton Heston’s character activated a doomsday bomb that obliterated Earth.

For Escape, Dehn crafted a brilliant continuation, with Zira and Cornelius, the sympathetic chimpanzees from the first film, helping to repair Heston’s spaceship. In an unexpected twist, the explosion of Earth sends the ship back in time to the past.

Escaping to the Past

The movie opens in 1973, where the Navy finds the spaceship adrift off the California coast, with the three chimpanzees aboard. They are quickly taken to the Los Angeles Zoo, where they must hide their ability to speak from the attending animal specialists, Dr. Lewis Dixon and Dr. Stephanie Branton.

However, Zira’s frustration at being forced to take an intelligence test leads her to speak out, revealing their secret. Shortly after, Milo, one of the chimps, is killed by a gorilla in the neighboring cage, leaving Cornelius and Zira feeling increasingly vulnerable.

But things take a turn when the two apes are questioned by a Presidential Commission. During the interrogation, they reveal their origins from the future, though they hold back the truth about their connection to Colonel Taylor and the fate of Earth.

This revelation leads to them being viewed as both fascinating and iconic, garnering fame and attention from the media and the public. The plot takes a darker turn when Dr. Otto Hasslein, the President’s chief science adviser, discovers that Zira is pregnant and begins to worry about the implications for the future of humanity.

He believes that Zira’s baby might become the ancestor of the intelligent apes who will eventually dominate mankind. This realization sets in motion a dangerous plan that threatens the lives of the soon-to-be parents.

A Change in Perspective

What Dehn manages to do so effectively is turn the tables, making the apes the objects of curiosity and fear in a society that mirrors their own, but in a manner that is entirely foreign to them. The film begins to echo the novel La Planete des Singes by Pierre Boulle, as the apes become a metaphor for society’s treatment of those seen as “other.”

In many ways, Cornelius and Zira are treated much more kindly by human society than the humans in the original Planet of the Apes were treated by their civilization, though the treatment still feels odd and out of place to the apes.

In the latter part of the film, Escape from the Planet of the Apes manages to achieve two key elements: it establishes the apes as the main characters, shifting the audience’s sympathy from humans to simians.

It also sets the stage for the cyclical nature of the series, where the actions of the apes now directly influence the future, creating a loop that repeats itself through time. The idea that Cornelius and Zira are essentially their ancestors brings the story full circle, with a direct link between past and future events.

A particularly striking moment occurs when Dr. Hasslein meets with the President to discuss the concepts of fate, free will, and destiny. Hasslein’s idea that killing Cornelius and Zira would be akin to preventing the birth of Hitler’s ancestors presents a chilling moral dilemma.

Although the President does not support this drastic action, Hasslein continues to press for it. The novelization by Jerry Pournelle adds an extra layer of complexity to this scene, where Hasslein suggests making the apes sterile instead of killing them, a proposition that still doesn’t sit well with the apes.

The Chase and Final Tragedy

As the film moves towards its final act, the tension builds, and Escape becomes a thrilling chase, with the apes on the run from Hasslein and the authorities. They find temporary refuge with a circus owner, Armando, but are soon forced to flee again, culminating in a heartbreaking showdown at an abandoned pier.

This tragic and violent climax echoes the dark endings of the previous Apes films. The final moments, in which Cornelius, Zira, and their baby meet a violent end, are both shocking and disturbing, especially given the film’s family-friendly rating.

Zira, in her grief, throws the dead baby into the water before crawling to her husband to die alongside him. In a last-minute twist, the baby Zira throws into the water is not her own, but that of a chimp from Armando’s circus, switched to give their child a chance at survival.

This setup promises a continuation of the saga, hinting at future films in the franchise. The structure of Escape from the Planet of the Apes laid the groundwork for a series where each film leads into the next, a practice that is now common in modern franchises.

Directed by Don Taylor, Escape was produced on a budget of just over $2 million, which was modest even for the time. Despite this, Taylor’s direction is competent, moving the story along smoothly.

With only three actors in ape makeup and locations set in contemporary Los Angeles, the production was simpler compared to the previous films. The return of composer Jerry Goldsmith also helped project the film, as he reworked his themes into a darker, more contemporary sound.

The performances of McDowall and Hunter are particularly noteworthy. McDowall’s portrayal of Cornelius evolves from the reserved scientist of the first film into a more protective and fierce figure, while Hunter’s Zira remains sharp and cynical but is softened by her role as a mother.

Supporting performances, especially from William Windom and Ricardo Montalban, further enhance the film, as both actors were well known in the sci-fi genre, particularly for their roles in Star Trek.

At the box office, Escape earned around $12 million, which, although modest by today’s standards, was enough to warrant a sequel. However, producer Arthur P. Jacobs was disappointed with the film’s promotion, believing that Fox relied too much on the Apes name rather than marketing the film itself.

Despite mixed reactions to Beneath, Escape received positive reviews and cemented itself as the best sequel in the original Planet of the Apes series. It would be followed by Conquest of the Planet of the Apes, which delved into even darker themes.

However, Escape remains a standout, thanks to its clever storytelling, mix of suspense and humor, and memorable performances.