Years after my initial viewing, I returned to “RoboCop” with the expectation of reliving some nostalgic ’80s moments. What I experienced, however, was far from sentimental.

Watching it again as an adult highlighted that “RoboCop” transcends mere entertainment; it stands as a cinematic achievement. Under Paul Verhoeven’s direction, the film masterfully combines substance and style, complementing its outrageous action sequences with deeper thematic content.

The satirical elements that I overlooked as a child have only grown more relevant with time, echoing the film’s warnings about corporate greed, unchecked consumerism, gentrification, and the militarization of police forces. All these themes are woven into a compelling narrative that explores humanity and the essence of the soul.

Paul Verhoeven’s direction elevates “RoboCop” to the level of a true masterpiece. While other filmmakers might have struggled to balance a film filled with heavy themes and splatter-filled action, Verhoeven seamlessly unites these threads into a thrilling conclusion that leaves viewers cheering. What’s not to appreciate?

The Plot of RoboCop

Set in a dystopian Detroit, “RoboCop” depicts a city overrun by ruthless criminals like Clarence Boddicker (Kurtwood Smith) and his gang. The beleaguered police force has fallen under the control of the ominous Omni Consumer Products (OCP), a corporation intent on profiting from its mechanized enforcers.

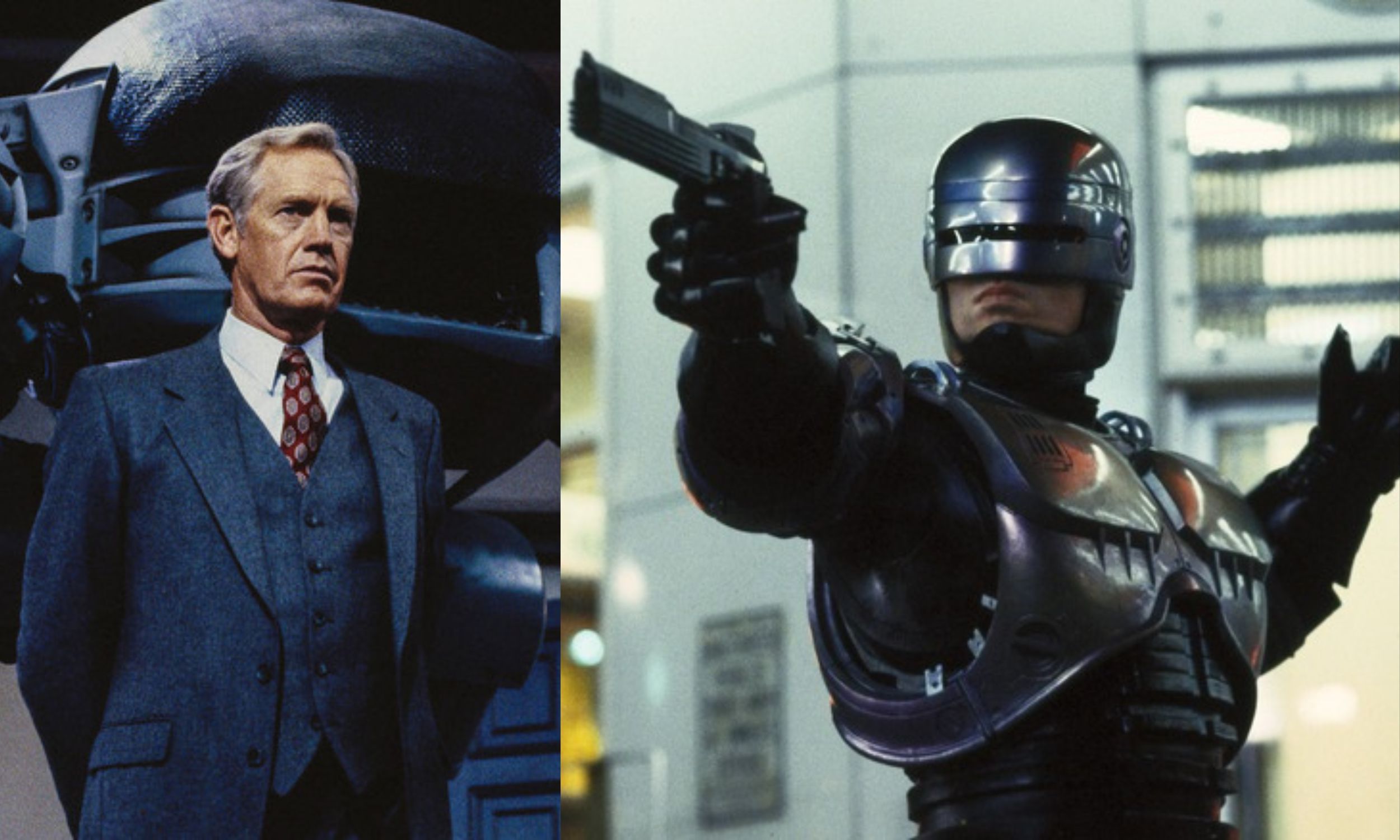

The villainous Senior President Dick Jones (Ronny Cox) seeks approval from his superior, “The Old Man” (Daniel O’Herlihy), to launch the ED-209 unit, a menacing walking gunship still plagued by glitches.

Following a disastrous boardroom demonstration, Jones’s rival, Bob Morton (Miguel Ferrer), seizes the opportunity to promote his RoboCop initiative, which promises a more human touch to cyborg law enforcement. All he requires is a “sucker” to volunteer for the project.

Alex Murphy (Peter Weller), a composed police officer and devoted family man, joins the Detroit West police department. He pairs with the tough Anne Lewis (Nancy Allen), and their first assignment leads them to confront Boddicker and his crew.

Without backup, Murphy meets a tragic fate at their hands. With Murphy dead, Morton has his ideal test subject, resurrecting him as RoboCop—a shiny robotic officer set to protect and serve.

He quickly takes down the city’s criminal underbelly but faces a hurdle: although his brain was wiped, remnants of his past life resurface, driving him to pursue Boddicker’s gang. This poses a threat to Jones, who clandestinely supports Boddicker to instill fear as part of his grand scheme.

Corporate Greed and Police in RoboCop

The satire in “RoboCop” critiques the excesses of capitalism and the “greed is good” mentality of the Reagan era, with OCP’s ruthless management of Detroit’s police force as the focal point.

The name Omni Consumer Products hints at their business practices. With interests spanning healthcare and the military, OCP exerts serious influence.

Dick Jones’s ambitious plan involves seizing Detroit’s crime-ridden areas to construct New Detroit, an epitome of soulless gentrification. To achieve this, he finances Boddicker’s gang to eliminate cops, spread terror, and displace the local population.

Jones also aims to roll out the ED-209 unit as the “next big military product,” despite its rocky trial run. A failed demonstration might not deter Jones, as he stands to gain from spare parts contracts regardless.

While Bob Morton’s RoboCop initiative is popular, its cynicism is evident. Police officers, now employed by OCP, must sign waivers transferring ownership of their bodies to the corporation if they die. Morton likely envisions producing multiple RoboCop units, creating a potential squad of undead officers patrolling the streets.

This concept seems to resonate with Murphy when he reassures Lewis after her injury, stating, “Don’t worry, they’ll fix you. They fix everything.” Thankfully, Lewis survives and remains human in “RoboCop 2.”

RoboCop as an American Jesus

Verhoeven has described RoboCop as an “American Jesus,” and the film certainly draws parallels to Christ. Alex Murphy enters this urban battleground as a somewhat detached, saintly figure, a quality emphasized by Peter Weller’s performance.

In a time dominated by muscular action heroes like Sylvester Stallone and Arnold Schwarzenegger, Weller offers a more ethereal presence.

Murphy’s execution by the gang serves as his crucifixion; he embodies a good cop sacrificing himself for our sins—specifically, the rampant capitalism that has reduced Detroit to a violent, drug-infested landscape.

The symbolism is clear, even if not overly emphasized. The scene is nearly as brutal as Jesus’s suffering in “The Passion of the Christ,” beginning with a shot that completely blows off Murphy’s hand.

Once he is declared dead, Murphy returns as RoboCop, Detroit’s savior. Verhoeven even depicts him as if he walks on water. While the metaphor exists, it doesn’t fully capture RoboCop, who represents an amalgam of various hero archetypes.

His signature move—spinning his gun before holstering it—harkens back to classic Western heroes, with a modern twist seen in his son’s favorite show, “TJ Laser.”

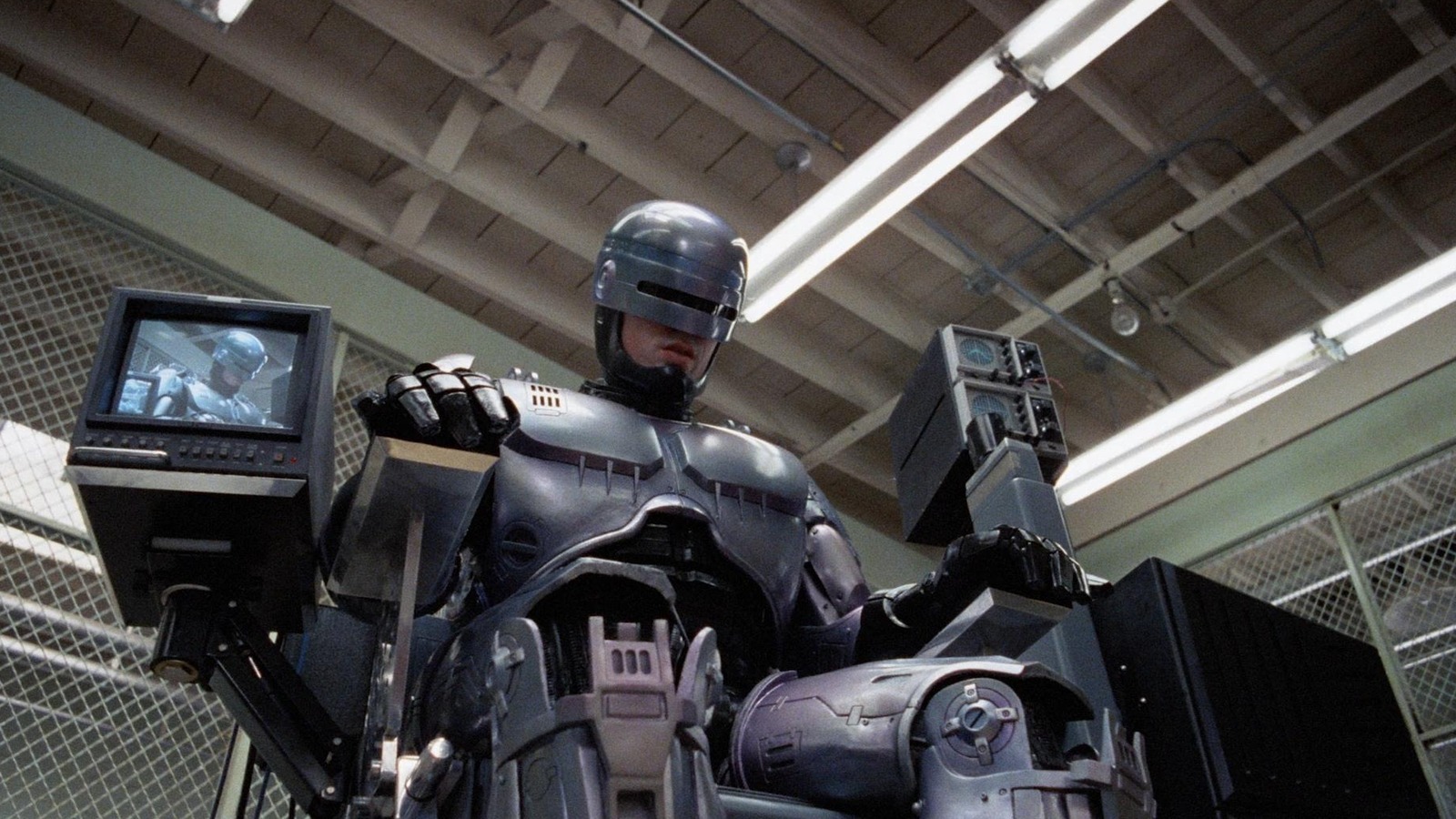

Additionally, RoboCop visually resembles a knight in shining armor, often filmed from below for dramatic effect, his suit shining brightly as he rescues a woman from two attackers.

The Human Element of Murphy

What draws me back to “RoboCop” is Murphy’s journey to rediscover his identity and humanity, beautifully portrayed throughout the film. The intertwining of pathos and violence enriches the story, leading to a powerful conclusion.

Despite having undergone a brain wipe, Murphy experiences flashbacks that prompt him to seek out his past. A poignant scene occurs when he returns to his former home, where visions of his wife and child fade as he walks through empty rooms.

This moment encapsulates his heartbreak: regardless of his discoveries, the original Alex Murphy is irrevocably lost, leaving only a spirit confined within the RoboCop framework.

If the soul signifies our humanity, can Murphy still be deemed human despite his cyborg existence? His memories may be erased, yet he retains the capacity for love and sadness over his family’s loss. The elements that define his humanity endure beyond his memory loss.

The extent of Murphy’s physical remnants is ambiguous. Bob Morton’s cold order to discard the arm that doctors managed to salvage implies that most of his original body has been discarded.

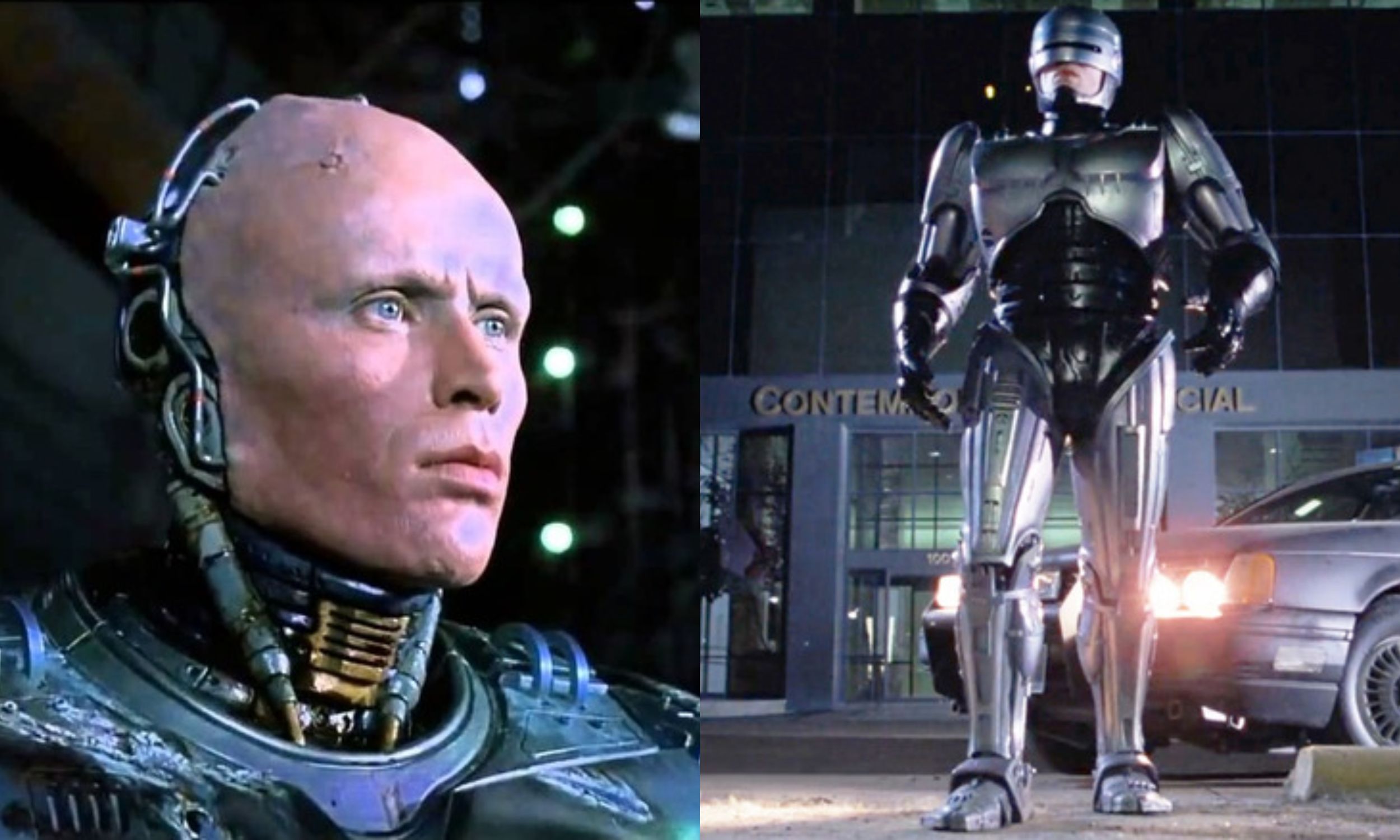

However, he retains his eyes, which play a crucial role in Murphy’s reclamation of his humanity. If eyes are the windows to the soul, Murphy’s remain concealed behind RoboCop’s visor for much of the film.

When they are finally revealed, they reflect deep sorrow as he comprehends what he has become, realizing he cannot revert to his former self. Yet, there is still one thing he can do: seek vengeance.

The Climactic Conclusion

Following the confrontation with Boddicker’s gang at the mill, Murphy and Lewis prepare to settle the score with Dick Jones. Previously, RoboCop was unable to apprehend Jones due to Directive 4, a covert failsafe that prohibits him from acting against OCP executives—essentially a corporate version of Asimov’s Laws of Robotics.

In a dramatic crash during a board meeting, Murphy uses his data spike to expose Jones’s true motives to the other executives. This clever twist showcases his use of the spike first to eliminate Boddicker, then to dismantle Jones’s career.